Keynote speech pronounced at the AJ NEWS Asia Pacific Financial Forum in Seoul, Republic of Korea, March 2018.

The recent plan announced by US President Donald Trump, to increase tariffs on a broad range of Chinese products exported to the United States, for up to USD 60 billion, and the counterveiling measures announced by Beijing, reinforce the feeling of an imminent trade war that is ready to burst between the two largest économies in the world.

A trade war would have far-reaching consequences on a global level, it would jeopardise the fragile recovery that the world economy has experienced following the 2008 global financial crisis. A bellicose new policy is now promoted by a country that has more often than not benefited from the expansion of trade.

There are three sets of factors for that. These three factors are deeply imbricated and connected with one another.

The first factor relates to the changing patterns of economic growth, trade and employment across the world, following the financial crisis.

The second factor relates to the breakout of the established political and social consensus within the advanced industrialised countries, – and first of all, within the United States -, following the 2008 crisis.

The third factor has to do with Donald Trump’s peculiar style of leadership and his embrace of negotiation tactics. This is often put forward, as the media love to hate this ‘bigger-than-life’ character, and to cast light on his exuberant style and defiant attitude. But, this is a comparatively minor factor when compared to the first and second ones.

The election of Donald Trump in 2016 and his nationalist economic policy agenda – over which there is now more clarity, despite the ‘sound and the fury’ that prevailed in the first months following Trump’s accession to power – can be almost certainly attributed to the second factor that is mentioned above.

Let us examine these factors one by one, focusing on the two most important ones.

The consequences of the 2008 crisis and the changing nature of globalization

The 2008 global financial crisis had immediate, easy to understand, consequences, namely the spread of banking crises and economic recessions – or significant growth slowdowns, which is pretty much equivalent – throughout the world. The leaders of the world’s most important economies – the so-called G20 Group, which acquired broad publicity and récognition during that period – dealt remarkably well with these consequences.

They managed to fix most of the ‘inherent vices’ of the global financial industry, focusing on the bailout and recapitalisation ‘too big too fail’ banking institutions, while reinforcing banking and financial regulations and self-insurance mechanisms – so-called bail-in clauses and resolution plans – to avoid a repetition in the future of the same contagion and feedback effects, that were observed between bancs and financial markets and between banks and sovereigns. They also managed to contain the kind of contagion from the financial sector to economic activity that was observed during the Great Depression of the 1930s. They did this through a coordinated, massive monetary and fiscal stimulus that was meant to prevent a global credit crunch, to support financial markets and to substitute, albeit temporarily, private demand with public demand.

The financial crisis also had more protracted, far-reaching consequences, which have been underestimated, at first, by many economists and prominent policymakers. As a matter of fact, it is now clearly acknowledged that the 2008 financial crisis caused a lasting contraction in output, first in the advanced economies, then in China and finally in the other emerging and developing economies, with the oil price collapse of June 2014 playing a key role in the case of commodity exporters. According to the OECD, among 19 OECD major countries, the median loss in potential output is estimated to be about 5 1⁄2 per cent.

Official estimations show that the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany have closed their output gap only in 2013-2014, while Japan and the other Eurozone economies – apart from Germany -, still struggle to recover to their pre-crisis trend growth levels. China is also growing significantly slower than before the crisis with two digit growth figures now considered a thing of the past.

These official estimations underestimate the magnitude of the output problem. Indeed, if we look at industrial production excluding construction, we find that the deviation from the pre-crisis trend is dramatic, between 20% to 30% of the baseline pre-crisis trend. Industrial production in the United States and Germany has barely recovered to its pre-crisis levels, which is still far short from pre-crisis projections. As for Japan, it has been trapped since the crisis in a low-output, low-capacity utilization trap. And for China, it is even worse as industrial production keeps on falling since the crisis.

This has, in turn, led to a depreciation of the global capital stock – due to a fall in gross industrial capital formation after the crisis, across the board. The ultimate consequence of this chain of developments is a lasting slowdown of total factor productivity (TFP) and of labor productivity, which is reflected by limited wage growth for the working middle classes. This is very clear when we look at inflation figures, which remain stubbornly low all over the world, despite massive monetary injections in the United States, Europe and Japan.

As a matter of fact, the 2008 crisis accelerated the desindustrialisation trend that has been developing in the western advanced economies since the 1990s. No western economy managed to reverse this long-lasting trend, with the notable exception of Germany, which stabilized its share of industrial output in GDP in the 2Ks, following the implémentation of major domestic reforms and a policy of export-led growth, notably to China.

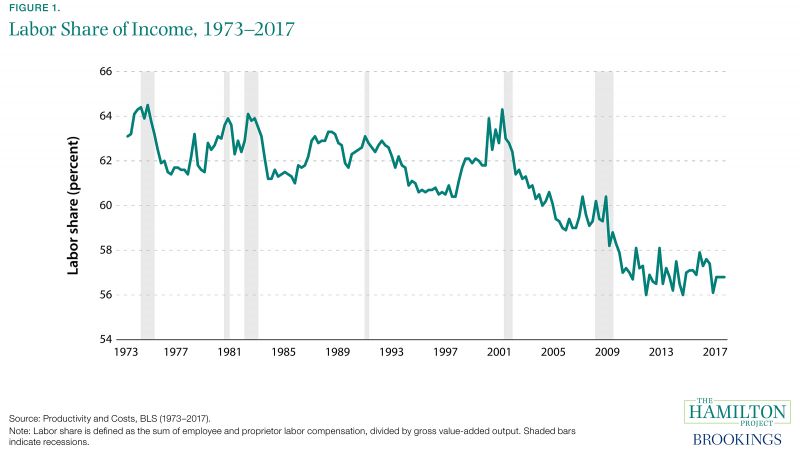

Following the Great Recession, the growing discrepancy between wages and stock market returns has been a critical factor behind the rising appeal of protectionism and economic nationalism , embodied by Trump’s Chief campaign strategist, Steven Bannon.

The problem of wage stagnation in the United States is not new. Indeed, a study conducted by the Brookings foundation shows that, after adjusting for inflation, wages in the United States are only 10 percent higher in 2017 than they were in 1973, with annual real wage growth just below 0.2 percent. This is compounded by the fact that wage inequality has intensified as higher paid employees saw their wages increase much more than lower paid jobs. Most of the above mentioned wage growth happened in the upper-middle and top wage quintiles. Over the same period the S&P 500 total return index delivered an average annual growth rate of 6.2%, after adjusting for inflation. But this has been much accentuated in the 2Ks as is illustrated by the falling labor share of income since 2001.

The industrial overcapacity problem has been underestimated

First, unemployment did not rise as much as expected in the core advanced and emerging economies in the first years after the crisis, or when it rose significantly, as in the United States, it receded quickly. which is surprising given the magnitude of the crisis. However, the official unemployment figures are biased by the rise of part-time employment – mostly in the US, the UK and Germany – and of underemployment in countries where the authorities managed to avoid massive layoffs, like in France and Japan for example, by inciting businesses to negotiate with the unions.

Second, and in a much related way, the coordinated response to the global crisis and the resulting huge monetary and fiscal stimulus that was implemented by the G20 economies, akin to a ’liquidity tsunami’, succeeded in supporting global demand in the short term, by substituting public demand to private demand, and by recapitalizing the banking institutions and easing financing conditions for corporations

However, the global supply overcapacity problem has not been suppressed. It reappeared through abnormally low-inflation all across the board, especially in Germany, Japan and China. Inflation is lower than the targets fixed by the major central banks.

Going forward, this may pose a problem as this impairs the capacity of monetary policy to react to new shocks. This is the so-called ‘zero lower bound’ problem which warrants the use of unconventional monetary policy measures. However, the latter distort financial markets and feeds asset bubbles

A new relationship between global trade and GDP growth

Another significant consequence of the global financial crisis is the slowdown of global trade.

Since the Second World War, the volume of world merchandise trade has tended to grow about 1.5 times faster than world GDP. In the 1990s trade grew more than twice as fast as gGDP. However, in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis the ratio of trade to GDP growth has fallen down to around 1:1 .

The weakness of trade growth is partly due to the continuing weakness in the global economy. But it also reflects deeper structural changes in the relationship between trade and economic growth.

Indeed, investment is the most import-intensive component of GDP and investment has been particularly weak in developed economies since the financial crisis, with sharp contractions in Europe in 2012 and 2013 during the sovereign dent crisis.

The contribution of investment to China’s economic growth has also declined, albeit more gradually. Investment accounted for more than half of China’s GDP growth in 2009-13, but by 2016 this had fallen to 39 per cent and it is expected to fall further going forward. This true for the two major forms of investment: housing and industrial investment.

This is explained by the Chinese authorities desire to rebalance China’s growth away from investment toward consumption and services. This has in turn had a major impact on the global trade in fuels, commodities and capital goods, of which China is the first importer in the world

Persistently high financial leverage and distorted markets

Another major legacy of the crisis, or more precisely, of the response to the crisis, is the build-up of leverage and the accumulation of debt across countries and sectors, the so-called ‘debt overhang’.

Figures from the IMF show that, leverage in the non- financial sector is now higher than before the global financial crisis in the Group of Twenty economies as a whole. Debt servicing pressures and debt levels in the private non-financial sector are already high in several major economies (Australia, Canada, China, Korea).

In China, banking sector assets have risen to represent now three times the GDP. The non-financial sector domestic credit-to-GDP ratio, which was stable at around 135 percent of GDP before the 2008 crisis, increased sharply to about 235 percent in 2016. Despite the Chinese authorities attempts to rain-in ’creative financial engineering’, the growing use of short-term wholesale funding and ‘shadow credit’ has increased financial vulnerabilities.

In a related way to the buildup of leverage and the delaying of the deleveraging process, the policies of the world major central banks have distorted markets Unconventional monetary policies channeled huge amounts of liquidity into capital markets, inflating asset prices and distorting relative valuations through a compression of risk premia associated with risky assets.

This has been achieved mostly through the purchase of government and mortgage-backed securities by Central banks in the United States, Japan and Europe, which crowded-out private investors from the sovereign market and pushed them to search for yield in other sectors and geographies.

The resurgence of financial volatility and the market correction that happened in the first quarter of 2018, is a reminder of the risks and vulnerabilities that has built-up. Going forward, more market volatility should be expected as majors central banks re-normalize their policies.

History shows that the perception of risk follows its own logic, and some valuations may prove to be unsustainable. This is particularly the case for high yield corporate bond markets and for some particularly exposed emerging markets (with debt refinancing needs and unhedged dollar liabilities), which may suffer from sudden risk aversion and experience capital outflows.

In order to mitigate the impact of market corrections and potential future financial crises, it is of paramount importance to finalize the regulatory reform agenda initiated by the G20 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Any national measures toward financial deregulation which would not be coordinated with the other G20 economies, and which will not be discussed within the Financial Stability Board, carry the risk of undermining the results achieved so far.

Outstanding challenges include the finalization of the banking union in the Eurozone, the framework for resolution of globally systemic financial institutions (GSFI), insuring effective cross-border coordination between regulators in case of emergency, strengthening the resilience of central counterparty clearing for derivatives, and an increased oversight and regulation of the so-called ’shadow finance’.

Particular attention should also be paid to private lending schemes and crowdfunding platforms, as well as to the so-called crypto-currencies. Although their notional volume is still relatively small, the observed correlation between the returns on ‘cryptos’ and on conventional assets during the market rout of Q1 2018, says a lot about their role as vectors of risk aversion.

The challenge to the multilateral order and what to do about it

Since the crisis of 2008-09, trade growth has slowed, while public skepticism about trade in some countries has grown. Trade has lifted hundred of millions of people out of poverty in emerging and developing economies. Evidence over 1993- 2008 shows that the change in the real income of the bottom 20% of the population in developing countries is strongly correlated with the change in trade openness.

However, the expansion of trade has also given rise to growing concerns among the low-income and middle-income classes of the advanced economies. The concerns have their roots in actual problems: prolonged low growth in many advanced economies; rapid technological change; rising inequalities and distributional effects of economic policies; widening productivity gaps among firms; and stagnant wages for many workers.

Across the OECD area, the average income of the richest 10% of the population is now more than nine times that of the poorest 10%, up from seven times 25 years ago. This is driven in part by a surge in incomes at the top end, and especially among the top 1%.

Many tax and benefit systems across the OECD area have become less redistributive, mainly due to working-age benefits not keeping pace with real wages, and taxes becoming less progressive. Expansions in the amount of tax revenue have been financed predominantly through taxes on labour and higher rates of VAT, affecting relatively more the middle class and low-income households respectively.

Inequality of opportunity is also increasing. Low income households are often unable to adequately invest in education for their children, which can have strong, detrimental effects and limit social mobility. Gallup trends since 2001 find Americans’ perceptions of foreign trade is divided along educational lines. College graduates and those with postgraduate education are significantly more likely to see foreign trade as an opportunity for the U.S. than are those with no college education.

In addition, not all businesses are sharing the benefits of globally integrated markets. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) tend to be under-represented in international trade. Long standing des-industrialization trends in the advanced economies, especially in the US and in the UK, and the resulting hundreds of thousands of job losses in manufacturing, encouraged negative perception of trade and globalization, although it has been demonstrated that these job losses owe at leas as much to productivity gains and technology evolutions as to increased openness and globalisation

As for the rise of inequality and wage dispersion, one major reason might be the fall in unionization rates in many OECD countries, as a result of a neo-liberal agenda that was implemented in the 1980s-1990s in most OECD countries. The other major reason is the growing gap between non-skilled and skilled wages, as increased international openness and the outsourcing of manufacturing production to low-wage countries such as China has weighed on non-skilled wages in the advanced economies

All in all, what is important to remind is that over the longer term, a failure to lift potential growth and make growth more inclusive in advanced economies could exacerbate the risk of a retreat from cross-border integration. This risk is real in a G-zero world is real and it is striking that the most established institutions, like the OECD and the IMF, or the most ‘oligarchic’ foras like the World Economic Forum all take now this risk very seriously.

The IMF even examines the idea of a universal income and proposes that governments raise their upper marginal income tax rates! However this would be impossible to be in a world, where some countries engage in a fiscal ‘race to the bottom’ to attract business investments and qualified jobs.

Trade disputes

A striking expression of the rising social discontent and its political channeling in decision making spheres is the growing number of trade disputes.

The international trade cooperation framework includes legally binding rules and dispute settlement mechanisms, centered at the WTO, a range of multilateral, regional and bilateral trade and investment arrangements, guidelines and ‘soft law’, such as those housed at the ILO and the OECD (e.g. the OECD guidelines on corporate governance of state owned enterprises).

It is fair to say that in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, WTO rules helped to prevent a slide into a 1930s-style trade war that would have greatly exacerbated the global economic crisis. Indeed, the WTO Antidumping and Subsidies Agreements permit WTO Members to impose antidumping (AD) or countervailing (CVD) duties to offset what is perceived to be outrageous dumping or subsidisation of products exported from one Member to another.

As a matter of fact, the number of notifications on anti-dumping and countervailing measures submitted to the WTO increased substantially after the crisis.

Metal products were subject to the most anti-dumping initiations, accounting for 36% of all initiations in the first period (June 2014-2015), 47% in the second period (June 2015-2016) and 41% in the June 2016-2017 period. In each period, at least 86 initiations targeted metals, of which 94% involved steel products (goods classified under Chapters 72 and 73 of the HS Code). Over the three periods combined, the United States (73), Australia (39), the European Union (29), Canada (25), and Mexico (21) accounted for more than half of the 333 initiations on metals.

Initiations on metals across the three periods targeted mostly products from China (88, of which 79 involved steel products), the Republic of Korea (35, of which 34 involved steel), India (20, of which 19 involved steel) and Viet Nam (17, of which 15 involved steel).

China remained, by some margin, the most frequent subject to anti-dumping initiations during the three reporting periods – accounting for 28% of all investigations. The Republic of Korea was second, accounting for 9% of total initiations, followed by India at 5%.

Among the fourteen Members that initiated countervailing investigations over the last three years, the United States initiated the most new investigations (60), accounting for 54% of initiations. The United States initiated 28 of the 56 countervailing investigations on steel products. Five of the 13 steel-related initiations in the current period involved products from China.

This is not a surprise as metals and particularly steel products are one of the items that are directly associated with the prevailing industrial overcapacity. The oversupply in the steel industry amount to a third of total production capacity. And this oversupply is located mostly in China, which tried to reduce it mostly through exports, hence translating into a dramatic drop in international steel prices.

The rising number of disputes has not been followed by an enhancement of WTO capabilities and resources. The functioning of the WTO dispute settlement system itself is today at risk as the renewal of four judges out of a total of seven that siege at the appellate body, has been, de facto, blocked by the Trump Administration.

This comes after US President Donald Trump expressed at many occasions his discontent and frustration with the WTO dispute settlement process – which is allegedly too lengthy, bureaucratic and biased against the US. However, he has not proposed any solutions or reforms that could fix this problem, or, enhance the capabilities of this multilateral organization.

So far, the Trump administration has adopted a confrontational stance and privileged bilateral trade bargaining and dispute settlement outside the WTO framework. The Trump administration also tried to tie trade disputes with other contentious issues such as military burden-sharing with its strategic allies, or the extraction of geopolitical concessions from its adversaries

How to fix and save the multilateral order?

All in all, this Administration seems no longer willing to play the sponsor and main guarantor of the international economic order that the United States carved out after the Second World War, and of which the GATT-WTO is a key pillar.

The perceived lack of efficiency of multilateral institutions is among the factors that affect the allocation of trade benefits, both within and among countries, sectors, workers and regions. This reflects negatively on the commitment of some members to the system, especially when these members are ’great powers’.

If left unchecked, this can lead to isolationist tendencies which could go as far as a unilateral withdrawal from the system or a ‘stealth veto’ impairing its functioning for the other members. A related concern is the perceived lack of legitimacy of multilateral institutions.

Therefore, there is a need to fix the existing gaps to make the international system more efficient and more legitimate for political and social constituencies and interest groups beyond the states. This might be achieved by the association of focus groups to the rule-making process and the establishment of consultative bodies that allow social interest groups to express their concerns.

The trading system for example is perfectible. Although there has been a significant reduction in tariffs since the inception of the GATT mechanism and of the creation of the WTO in 1995, non-tariff measures, subsidies and local content requirements remain pervasive.

These measures are often taken on other grounds than trade such as industrial policy or social and territorial cohesion. However, they may negatively impact trade partners which have their own political constituencies. This makes it important to develop dialogue on a multidimensional level in order to solve the resulting disputes in a multilateral manner, and to avoid the proliferation of ‘beggar thy neighbour’ policies.

More broadly speaking, critical issues such as labor conditions, food security, public health, climate change and international migrations are all treated through distinct organizations, and separate jurisdictional and monitoring processes. This translates into a set of policies and framework that can sometimes lead to conflicting outcomes and non-cooperative decisions.

There are examples of successful cross-institutional cooperation for example on food safety and consumer protection, between the WTO and the Codex Alimentarius, which is itself a joint initiative of the FAO and of the WHO. The financial stability board is another example of a successful cross-institutional and cross-border cooperation which associates governments, central banks and financial industry representatives.

Another area of progress is the harmonisation between the multilateral framework and the bilateral or mini-lateral initiatives that might be taken by a group of countries, which are willing to use the system to enhance their cooperation. This principle is for example enshrined since 2011 in the constitutional treaties of the European Union, allowing for more efficiency between a ‘coalitions of the willing’ while preserving the interest of other members.

This is particularly important in trade matters as there is a rising number of regional agreements which are negotiated outside the WTO, including so-called ‘deep trade agreements’ , which can undermine the centrality of the multilateral system and its relevance in the long term.

Finally, there is a room to reform the multilateral ‘agenda setting’ mechanisms in order to make it more forward-looking while at the same time defining a strategy that is consistent with the agenda of the most important nations – namely the G20 group.

In conclusion, the multilateral system can be saved from isolationist tendencies only by proving its relevance and its capacity to accommodate the ever-evolving power balance between states while at the same time sticking to its principle of equal access.